Fiction is psychology; psychology is fiction!

Jim Bird

Sunday.

Hi there, she thought, I’m Margo Penn-Jennings (inquisitive pause) and I’m here for the (sardonic pause) self-help seminar.

She did not like the sound of this in her head. The tone of her inner voice was prim, nasal, and superior. As she crossed the hotel lobby and approached the check-in table, with its giant HEALTHY SELF banner hiding the legs of the women who sat behind it, Margo resolved that she would not say anything like this, but instead, simply, whatever popped into her head.

“Hi there,” Margo heard herself say, “I’m Margo Penn-Jennings and I’m here for the self-help ... thing. Ha.”

You’re an idiot, her mind told her.

The women behind the table, in a flurry of uncoordinated activity, located her name on their list, had her sign in, produced a bundle of pamphlets and booklets held together with elastic bands which they called “the material,” and scolded her affectionately for being late. “You almost missed Jim Bird’s opening learning.” They said the man’s name like it was a single word, like he was a kind of bird—a jimbird.

“But ...” She began rummaging in her purse for the timetable that would exonerate her. “The seminar doesn’t start till tomorrow I thought.”

“Oh no,” said one of the women, “this is a spontaneous event.” She uttered these last two words with so little emphasis that they sounded capitalized, as if “Spontaneous Event” were one of the fundamental kinds of stuff in the universe. “You can leave your bags.”

Margo entered the already hushed convention room and, with her dogged instinct for thrift, took a seat among the “better” ones near the front. There were many chairs still vacant. Evidently she was not the only one to arrive late.

The portable stage was also empty, and remained that way for ten more minutes. The audience did not seem to mind. Their coughs were politely muffled; their chairs creaked softly, as if they were only settling more deeply into them; no one spoke. Margo turned and looked around the room, smiling when others’ eyes met hers. They all looked disgustingly normal.

At last a man got up on the stage, apparently to inspect the microphone. With a shiver of pleasant indignation, Margo felt sure that they were about to be told that the spontaneous event had been spontaneously cancelled.

“You’ve all made a mistake,” the man said, his amplified voice booming at them from every direction, making Margo jump. “You shouldn’t have come. There’s nothing wrong with any of you. Acknowledging you have a problem isn’t the first step towards fixing the problem—it is the problem.”

The man on stage, Margo realized, was none other than the jimbird himself.

Pay attention, she told her mind.

You shut up, said her mind, I’m trying to listen.

*

“You will become what you are.”At nineteen, Jim Bird read these words and found a bitter solace in them.

He was, at that time, grappling with free will. This was, to him, no airy philosophical inquiry, but as pertinent as a speeding ticket. He had treated a girl badly, and the question that weighed on him was whether or not he was to blame for his behavior—whether or not he was to blame for who he was, for he knew deep down that in his dealings with the girl he had acted only in accordance with his own wishes. The question was, therefore: Could he have wished otherwise? Could he someday want to do right, or was he doomed by a shabby character to act always in perfect self-interest? He hated himself for the way he’d treated the girl; but if he could not have acted differently, then surely it was pointless to hate himself.

Could he change himself? Could he choose who to be, or was his character immutable?

He found the answer he was looking for in Nietzsche.

The individual is, in his future and in his past, a piece of fate, one law more, one necessity more in everything that is and everything that will be. To say to him “change yourself” means to demand that everything should change, even in the past.

Because human beings take themselves to be free, they feel regret and pangs of conscience. But no one is responsible for his actions, no one for his nature. Judging is the same as being unjust. This holds equally true when the individual judges himself.

The sting of conscience is, like a snake stinging a stone, a piece of stupidity. Never yield to remorse, but at once tell yourself: Remorse would simply mean adding to the first act of stupidity a second.

Though this wisdom did not permit Jim to forgive himself or even stop hating himself, it did make him feel better. It was a kind of relief to establish, once and for all, that he would never be a better person, that he would never be able to rise above his despicable nature. In fact, admitting his worthlessness gave him a kind of intoxicating satisfaction. He had begun to like hating himself. “Whoever despises himself,” as Nietzsche said, “still respects himself as one who despises.” This may seem paradoxical, but it is the nature of hatred: One always loves oneself for hating. It is good to hate evil, and that which we hate is always, ipso facto, evil. I have always thought “righteous indignation” to be a tautology, for the greater the indignation, the greater the sense of righteousness. As humans we may love, but it is only as angels that we hate.

This is why hatred is such a pernicious pleasure. The more despicable we make the object of our hatred out to be, the more saint-like we feel ourselves to be by comparison. Sometimes, to savor our righteous indignation even more piquantly, we will actually cooperate with our tormentors, and stick our neck under their bootheel. I met a woman once who, feeling she was being cheated by a shopkeeper, in a fit of rage threw down twice as much money as her bandit was actually demanding and stormed out triumphantly. She liked this story, which she told again and again with bitter satisfaction, not because it showed she had done anything particularly wise, but because it showed she had been wronged—gloriously, angelically wronged.

Hatred is as much self-aggrandizement as it is other-deprecation; and the strange paradox of self-loathing is that it engenders such self-respect.

This can operate the other way, too. Margo, attending Jim Bird’s Healthy Self seminar years later, would write in her journal, “Of COURSE I hate myself. What self-respecting person doesn’t hate herself?” If nobody’s perfect, if all of us are flawed, then liking yourself can only be the most obscene arrogance. Whoever respects himself must despise himself as one who respects.

Jim Bird, at nineteen, felt that he had, as Nietzsche promised, become what he was. He was (as the girl he had wronged had told him) “a real shit.”

It was only years later, when his wife left him, that Jim Bird was at last able to stop hating himself.

*

“It’s not about you,” she assured him with maddening benevolence. “I am the only one responsible for my own happiness. I have to choose me.”She had just returned from a self-help seminar.

She removed her belongings from the apartment with the precision of a surgeon excising a tumor, without disturbing any of his things—thus dispelling the illusion that their lives had become intertwined. He saw not respect but contempt in the way she left his things so fastidiously untouched. Even his books stood uncannily upright on the shelves, none toppling over into the vacated spaces.

But she had, he discovered, left behind (accidentally?) a few of her self-help books.

Instead of ripping them in half or throwing them out the window, he read them—and this, through the ravaging haze of his hatred, felt like the more destructive act.

*

Smile, they said. This was the pith of their wisdom. Smiling was the panacea. The way to be happy was simply to be happy. We aren’t unhappy because bad things happen to us—oh no. We’re unhappy because we frown. So instead of frowning when bad things happen—smile!Citing everyone from Milton to Emerson (but especially Emerson), these self-help gurus asserted that we only ever experience the world through our own consciousness. A man does not enjoy Paris, he enjoys himself in Paris. If the world seems gloomy to you, it is because you are gloomy. Events and circumstances are in and of themselves neutral; how else explain the commonplace fact that the same event or circumstance can make one man happy and another sad? Therefore it is pointless trying to change the world. In order to achieve contentment, you have only to change your response to the world. When “bad” things happen, call them “good.” When life gives you lemons, visualize lemonade. When the world frowns, just smile.

Even if you didn’t believe you were happy, you should go through the motions, act like you were, and eventually happiness would come to you. How this would happen was left mysterious, but often the faith was couched in a sort of magical thinking of the like-attracts-like variety: Happy people attract happy people, happy thoughts attract happy outcomes. This was the power of positive thinking, of mind over matter, of dreams over reality: If you only imagined it vividly enough, if you only desired it strongly enough, it would be yours.

And this kind of thing, Jim realized with growing horror, was infiltrating popular consciousness in countless ways. It was now considered bad manners to be or even to look unhappy, because it was supposedly within your power to be otherwise. Colleagues, students, and complete strangers had come up to him and told him to smile. “It takes less muscles to smile than to frown,” they informed him (thereby exhibiting in a single sentence (1) the egoistic conviction that personal happiness was the highest goal of human life, (2) the slothful belief that what was easy was always preferable to what was hard, and (3) further evidence of the inexorable degradation of the English language: they should, of course, have said “It takes fewer muscles to smile”). Athletes in interviews no longer attributed their successes to practice or talent, or their failures to bad luck or inferior skill; nowadays, it seemed, the winners were always those who had wanted it more. “We just went out there and gave 110 percent,” they shrugged, with the implication that the other guys must have given 109 percent or less. Even Bird’s students lately seemed to believe that their grades should reflect not their performance but their desire or the degree of their commitment. “But I’m not a B-student,” they’d say, after putting in what they felt was an A-student’s effort; or, even more bluntly: “I really need this A,” by which they meant, of course, that they really wanted it—and wasn’t wanting something badly enough the necessary and sufficient condition of getting it?

But the philosophy of self-help was not just silly, it was potentially dangerous. Self-help, it seemed to him, could actually do harm. It did this in two ways: it put too much emphasis on the “self,” and too much emphasis on the “help.”

By telling you repeatedly that (he recalled his wife’s words) you were the only one responsible for your own happiness, self-help also implied conversely that your unhappiness was your fault alone. Never mind that your children were ungrateful or your boss an insufferable prick: if you were unhappy at home or at work, that was your choice—you were doing it to yourself. This was victim-blaming at its most flagrant. Now, instead of just being miserable at work, you were made to feel additionally miserable for feeling miserable. Furthermore, the absolute emphasis placed on “self” could only encourage meekness and docility. Don’t rock the boat—it’s not the boat’s fault you’re unhappy! This was, as Henry James said of stoicism, a philosophy fit only for slaves, for it taught men to embrace the status quo. But what if the status quo really were to blame? Self-helpers were told, when faced with injustice, to find inner contentment; but when confronted with a genuine evil, was it not suicidal to pretend that everything was fine?

“It is important to eliminate from conversations all negative ideas,” said Norman Vincent Peale, arch-prophet of positive thinking,

for they tend to produce tension and annoyance inwardly. For example, when you are with a group of people at luncheon, do not comment that the ‘Communists will soon take over the country.’ In the first place, Communists are not going to take over the country, and by so asserting you create a depressing reaction in the minds of others. It undoubtedly affects digestion adversely.

It would only have been necessary to replace “Communists” with “rampant militarization” or “the attenuation of civil rights” or “the exploding gulf between rich and poor” to update this advice to the era and milieu in which Jim Bird read these words. There were times, surely, when a little dyspepsia was justified?

Then there was the emphasis put on “help.” A cure always implied a disease. The incredible proliferation of self-help manuals over the past fifty years sent at least one clear message: You need help. “Ask yourself whether you are happy, and you cease to be so”; with so many books and magazines and television shows shrilly asking you, again and again, “Are you happy? Are you happy enough?” was it any wonder that people began to doubt that they were happy, or happy enough? With so many medicines being offered, how could one feel healthy? The solutions being offered were themselves the problem. No one ever acquired happiness by grasping at it.

Bird catalogued his criticisms methodically, as though it were his job. For indeed, the idea for a new project had begun to take form. He would write a book, scholarly and caustic, condemning the self-help industry. He needed a new project. It was five years since his first book had been published. An analysis of Nietzsche’s conception of the will, the book was more successful than it should have been, for it had appeared at a propitious time. Nietzsche had been prophetic in many areas, but his belief that volition was an illusion, merely the subjective experience of a system of semi-independent urges blindly colliding like chemicals in a beaker—this view of the mind seemed tailor-made for the so-called “Decade of the Brain,” when neuroscientists and psychologists alike strove to map all the parts of the personality onto sections of grey matter, hoping thereby to prove that we are nothing but our brains and therefore as much in thrall to the rigid laws of cause and effect as any other physical system. One of the lions of this movement, a famous philosopher who wrote popular books on materialistic determinism (as it was called), even provided Bird’s book with a lengthy introduction, in which he generously (if somewhat anachronistically) indicated the ways in which Nietzsche’s views echoed his, the philosopher’s, own: “The will, as Nietzsche would be the first to admit, is, like consciousness itself, an illusion. What we call ‘will’ is just the shorthand employed by a complex machine to signify what I have elsewhere called ‘self-referential subroutines’ ...” etc., etc. Bird’s own name was not mentioned in this introduction, nor indeed were the ideas he presented in the text; Bird was not sure the famous philosopher had even read his book. Nevertheless, for this service, the philosopher’s name appeared on the cover in a font that Bird (with a ruler) determined to be only two point-sizes smaller than his own. But the book sold well, and Bird’s academic future was assured.

The Decade of the Brain, however, had come and gone, and whether or not it had achieved its objectives, Bird knew that he wanted nothing more to do with anything that might appeal to neuroscientists, psychologists, or famous philosophers. He wanted to do something different. Here, at last, in self-help, he had found something different.

But he was afraid that to write this attack on self-help as a philosopher, to write this book as a piece of scholarly and caustic social criticism, would be to write over the heads of the very masses who consumed the stuff. An academic treatise would be “academic” in the worst sense of the word: detached, theoretical, dry—“merely academic.” You could not denounce the populace from an ivory tower; you had to descend to the streets, like Zarathustra. Bird wanted, more than anything, to address his attack to self-help’s adherents. He wanted to write something that his wife might read.

The only way to do that was to speak in their idiom, to adopt the language of the self-help books themselves.

He would write a self-help book to end all self-help books—an anti-self-help book. He would write a satire.

*

The writing came easily. Almost too easily—for, as Nietzsche said, “The sum of the inner movements which a man finds easy, and as a consequence performs gracefully and with pleasure, one calls his soul.” Till now, Bird had taken it as axiomatic that writing was like giving birth: there had to be labor pains. In the past he had never been able to produce more than four or five hundred words a day, for he could not commit a single sentence to paper without becoming paralyzed by the thought that this one idea could be written a million different ways. Nietzsche said that the great writer could be recognized by how skillfully he avoided the words that every mediocre writer would have hit upon to express the same thing. Bird, who wanted only to be understood, would struggle desperately to hit upon those mediocre words; but everything he produced looked awkward, unnatural, flamboyantly recherché. Now, for the first time, the words suggested themselves. He turned out a thousand, fifteen hundred, two thousand words a day. He felt himself almost physically taken over by the project—much the same way (or so he imagined) that Nietzsche had been taken over by the writing of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It was as if this was what, and how, he had been meant to write all his life; and this thought, so damaging to his scholar’s ego, was the only dark spot on the otherwise ecstatic joy of composition.He found that he could mimic the self-help books’ conventions almost effortlessly, and indeed with pleasure, for in this medium that he had no respect for he could let himself go completely. Like a patient playing a villain in a psychodrama, he was free to say and do things he would never have said or done in his own person. It was downright cathartic.

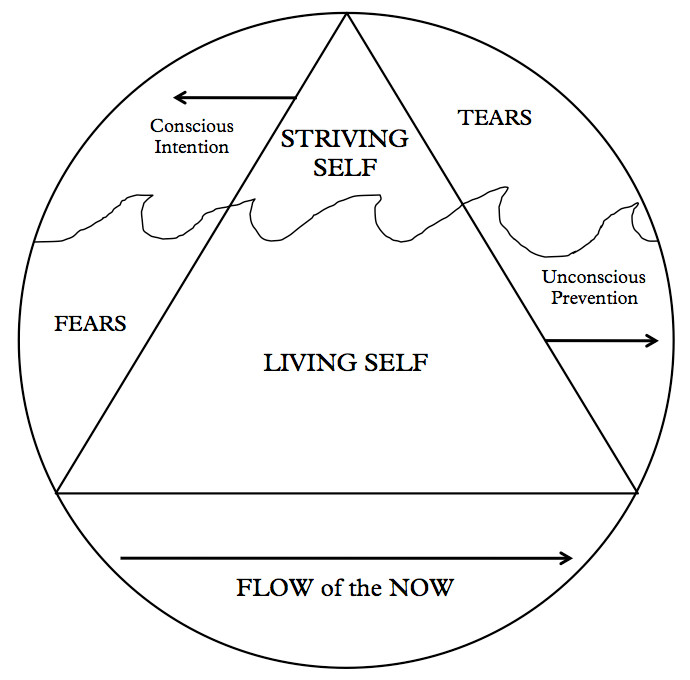

He easily mastered the loose (i.e., ungrammatical), chatty (i.e., slangy), chummy (i.e., badgering) prose style, and had a knack for turning out phrases that could have been self-help boilerplate: “If you don’t give in to your true self, your true self will give in to you.” “Smiling is not a panacea—but it is a good cure for a frown.” He managed to sustain the requisite tone of manic enthusiasm for over 300 pages through an unending barrage of italics, underscoring, boldface, capital letters, funny fonts, and other typographical tricks for signaling emphasis. He disguised his extended sermon as an interactive dialogue by putting a lot of obtuse questions into his reader’s mouth (“I know, I know, you’re thinking: But does this really apply to me?”) and then answering them (“You bet it does, buster! It applies to everyone”). He borrowed the authority of great thinkers of the past, quoting everyone from Milton to Emerson (especially Emerson)—everyone, that is, too famous for first names. He capitalized dubious concepts and gave them Unnecessary But Impressive Abbreviations (e.g., UBIAs). He manufactured supportive anecdotes and testimonials as needed. He employed a sort of pietistic scientism, citing “recent scientific studies” to demonstrate anything he wanted to demonstrate. He adopted at times a plodding conscientiousness, making clear what was already clear, defining terms in no need of defining, providing several synonyms for commonplace words, as if combating not just the reader’s skepticism but their unfamiliarity with the English language. He was shamelessly repetitive, writing the same sentence several times in a single chapter, often verbatim. He summarized chapters in forewords and again in afterwords. He filled entire pages with synoptic tables and lists. (Self-help authors loved lists, especially lists with seven or ten items.) He created an outrageously transparent self-quiz which claimed to help the reader measure their “striving index,” that is, the degree to which they overexerted themselves. (Question number 47: “Do you exert yourself excessively? Never. Rarely. Sometimes. Often. Always. (Circle one.)” Question number 89: “Are you the kind of person who ‘overdoes’ it? Never. Rarely. Sometimes. Often. Always. (Circle one.)”) He drew beautifully absurd diagrams of abstract ideas or psychological entities that were simply not susceptible to pictorial representation, and chuckled happily over them:

So (some of my readers may be forgiven for wondering), if Letting Go was written as a parody, a joke—then Jim Bird is a fraud? All his bestselling books, and the lucrative seminars spun off from them, are just a big hoax?

Not so fast, buster.

It is true that, soon after Bird sent the manuscript off to his agent, the joyous inspiration of composition faded and he ceased to think very highly of the project. It had been a distraction when he had needed one. It had siphoned off some of the anger he felt towards his wife. It had been, he supposed, a kind of primal-scream therapy. But now, in the deafening silence with which his agent received the manuscript, Bird felt acutely embarrassed by his cathartic howls. A person’s respect for their own accomplishments is usually proportionate to their efforts; because Bird had not experienced any labor pains, he could not feel as though he had given birth. The manuscript was not his child, but something he had sloughed off. He had produced it as he grew hair, and once one’s hair becomes detached from one’s head, one tends to view it with disgust.

His agent, a broker of scholarly monographs to university presses, understandably did not know what to make of the manuscript. Whether or not it was intended as a joke, she did not think it was likely to help her client’s academic career. So she sat on it, and did nothing. When, a year later, Bird wrote to ask if he could shop it around to publishers himself, she readily consented. (Later still, when the book appeared and soon shot to the #1 spot on the New York Times “advice” bestseller list, where it would stay for seventeen weeks, she casually consulted her lawyer to find out if she might still be contractually entitled to some of the royalties. She was told that it would depend on whether or not Bird had kept a copy of her consenting letter. The agent decided not to pursue the matter; instead, to savor the delicious sense of having been wronged, she annulled her contract with Bird herself.)

For a year, Bird was content to leave the book alone. But when he finally picked it up and read through it again, he was surprised. Because he had had time to forget much of it, and because it was not written in his usual labored style, he found that he could almost read it as the work of someone else—which is, of course, the best possible way to read one’s own work.

It was undeniably silly, and dumb, and sloppily written—but then, he thought, so were all self-help books. And this was undeniably a self-help book.

But this one was different. This one said something he agreed with. This author, he felt, had gotten something right.

You are (this author wrote) a piece of fate. Your body and your mind are governed by physical laws and necessities. That means you yourself are a law and a necessity. To improve yourself—to change yourself—it would be necessary to change the laws and necessities of the physical universe!

Because you think you should be able to improve yourself, you feel pain and anguish when you fail to do so. You beat yourself up for not being better, for not being different. But NO ONE is to blame for who they are or who they are not!

Hating yourself for not being someone else is like hating a rock for being a rock. It’s not being you that makes you unhappy, it’s wanting to be someone else.

You are who you are. You can’t be anyone else. Why would you want to be?

This, to Jim Bird, sounded familiar, and true. He had, it seemed, almost despite himself, written something of value. It was not a spoof, but an antidote.

When he sent the manuscript to several of the most prominent publishers of self-help books, he did so with some lingering shame (which was not much alleviated by signing his cover letters “Jim Bird” instead of “James R. Bird, Ph.D.”). He still feared, at this point, that someone would see through him, would see that he was only joking. This fear finally began to diminish when the book was enthusiastically accepted by a large and powerful publishing house. It diminished further when the book was launched, and still further when it began to sell in astounding numbers. No one called him a fraud. No one said, “But you’re just a philosophy professor at a cut-rate university. What do you know?” On the contrary, letters began to pour in from across the country assuring him that he had said something true, something of value. He began, naturally enough, to believe it. He resigned his tenure at the university. He began to receive, and then to accept invitations to speak in public, to sign books, to be interviewed on television. He started to plan a second book, one that would rectify the flaws of the first, clear up some of his readers’ misconceptions, and forestall further misreadings. By the time his ex-wife accosted him after one of his sold-out lectures, the feeling that he would be exposed as a sham had been almost completely extinguished.

“You’re looking well,” he said, sincerely and with a lack of malice that astonished himself. He noticed that she wasn’t holding a copy of his book.

“You,” she said, “are looking like you’re making a tremendous fool of yourself.”

After that, the self-help guru took his new career very seriously indeed.

*

Monday.

“Hi everybody, I’m—”

“Could you stand up for us?”

The girl stood awkwardly. “Well, I’m Sonja, and one thing about me is that I’m a waitress and a single mom.” She got it out in one breath and sat back down. Margo smiled and clapped softly, but no one joined in.

Be quiet, she told herself.

“Now Sonja,” said Ethan, pressing the tips of his index fingers against his lower lip, “is waitressing something you are, or something you do?”

Not sure whether to stand again to answer, she hovered briefly, half-crouched, above her chair. “Something I do?”

And so it went. “Tell us, John, are your grandchildren something you are, or something you have?” “Now Lottie, do you think jogging is something you are, or something you like?” Everyone sheepishly agreed that what they’d thought they were was actually just something they did or had or felt or liked.

At first Margo didn’t understand; surely “single mom” was not just something you did? But then she was reminded of an activity they’d done at Personal Pursuit, the “rock-bottoming” exercise. The instructor kept asking variations on the same question; the idea was to dig deeper, to evaluate your stock responses, to unearth what you really meant or really felt about something. This in turn reminded her of the Martian exercise they’d done at Best You: “I’m sorry, I’m from Mars, what do you mean by ‘single mom’? ... What do you mean by ‘not married’? ... What do you mean by ‘relationship’?” There, the point had been to peel away the layers of assumptions and conventions, to strip away the veneer of the self you presented to the world, and reveal the precious, if perhaps unlovely, self as you saw it. Maybe this was like that.

By the time Ethan pointed his praying hands at her, Margo had prepared and mentally recited what she felt was an unobjectionable introduction.

“Well Ethan, and everybody, hi. I’m Margo, though mostly folk call me Mar. In order of personal importance, I am ... the proud mother of two wonderful and successful grown daughters, I am the co-owner and part-time manager of a flower arrangement and delivery business, I am an actor and a playwright, I am a novice watercolor painter, I am a hobby gardener, I am a former—”

Ethan cut her off: “Now, Margo, is painting something you are, or something you do?”

She’d known it was coming, but still the question perplexed her. “Well Ethan, painting is certainly something I do, but painter, I think, is something I am ...”

“Are you a painter, or someone who paints?”

She saw his point, or thought she did: she was just a dabbler. But she hadn’t claimed to be a professional. “Someone who paints, I guess.”

He accepted this as conclusively damning and shifted his attention to the next woman.

“Wait a second,” she said. (Shut up, her mind barked at her.) “Isn’t what you do part of what makes you who you are?” She looked around the room for support, and found it: everyone was smiling mildly and nodding at her.

“Let me turn that around and give the question back to you, Margo. If driving home one night you—God forbid—ran someone over, would that make you a ‘murderer’?”

She was too flabbergasted to say anything more than “I guess not.” After a moment’s reflection she wanted to ask if she’d run over this person on purpose, then realized that this was not the crux of the matter. Yes, she thought, if I killed someone, that would make me a killer—wouldn’t it? But it was too late to argue. Everyone was already smiling and nodding at the woman next to her, whose name Margo had missed.

*

Tuesday.

He was fortyish, he smelled good, and his name was Bread.

She smiled her two-thirds amused smile. “Bread?”

“Bread,” he repeated.

She felt the smile going stale. “Brett?”

“Bread,” he said. “With a D.”

Finally it dawned on her. He had an accent.

“Oh, Brad!” she almost shouted, then felt stupid: she sounded like she was correcting his pronunciation of his own name.

“Two minutes,” called Ethan, “starting ... now.”

She had offered to go first. So she started talking.

*

One of the problems with self-help books is their smug, apodictic tone—the way they make sweeping declarations, as if these were established facts applicable to everyone at all times. But anyone who has cultivated the moral belief that we are all unique individuals with unique needs will bridle at the notion that one size of advice fits all. Reading these books’ prescriptions, we quite naturally and instinctively start to imagine scenarios in which, or people for whom, this advice would be laughably inappropriate—or even disastrous. For example, I found myself, when reading John Gray’s really quite harmless “101 ways to score points with a woman,” picturing all the women I knew who would be somewhat less than swept off their feet by your “offering to sharpen her knives in the kitchen” (#63), showing her that you are interested in what she is saying “by making little noises like ah ha, uh-huh, oh, mm-huh, and hmmmm” (#80), or “letting her know when you are planning to take a nap” (#23). It was also good cynical fun to dream up men for whom “treating her in ways you did at the beginning of the relationship” (#61) or “touching her with your hand sometimes when you talk to her” (#78) would be bad advice. Try it yourself.This is just what William Gaddis does in his novel, The Recognitions. He lampoons the cult of Carnegie through one overearnest disciple, Mr. Pivner, who applies the principles of winning friends and influencing people even when being accosted by a crazy man on a New York City bus. Even “at this critical instant,” his training does not fail him: he recalls chapter six, “How to Make People Like You Instantly,” which advises him to find something about the other person that he can honestly admire.

—What a wonderful head of hair you have, said Mr. Pivner. The man beside him looked at the thin hair on Mr. Pivner’s head, and then clutched a handful of his own. —Lotsa people like it, he said. Then he sat back and looked at Mr. Pivner carefully. —Say what is this, are you a queer or something?

Mr. Pivner’s eyes widened. —I ... I ...

This is funny, if not exactly convincing. Why, for instance, does Mr. Pivner want to make this man like him instantly? To blame Dale Carnegie or his book for this silly exchange is not quite fair.

Most of the criticisms of Jim Bird suffer from the same sort of straw-man irrelevance. It is all too easy to imagine people (serial killers and pedophiles are most commonly adduced) who perhaps should not be encouraged to accept themselves, or to stop striving to change who they are. But what about the average person? What does someone of average intelligence with average-sized problems get, or not get, out of a Healthy Self seminar?

What Margo had hoped to get was a little inspiration. This was her fourth self-improvement seminar. The first one, which she had attended nearly ten years ago, had helped her get over, or “get past,” her husband Bill’s death. The second one had given her the courage to change careers—to give up acting. The third one, three years ago, had revealed to her that her daughters no longer depended on her and that she had the right to pursue her own happiness; that is, it had helped her to move out and remarry without guilt. Now, having left Bertie, her second husband, and moved back home, she knew only that she needed to change her life again. She was 55 and didn’t know who she was or what she should be doing. She felt as though she had forgotten her lines, misplaced her script. At night, in bed, she couldn’t sleep, because she didn’t know what to do with her teeth: if she held them together, she felt as though she were clenching her jaw; if she held them apart, she felt as though she were gawping. Nothing felt natural anymore. Nothing felt normal.

*

She told some of this to Brad, but found it difficult to concentrate with him staring at her. When it was his turn to speak, she found it even more difficult to listen. They were sitting, as instructed, facing each other, with feet flat on the floor, hands on knees, and backs straight. This posture did not make her feel “open,” “receptive,” or “attentive,” but stiff and ridiculous, and this sense of her own ridiculousness acted as a far greater barrier to receptivity than crossed arms or slouching ever could have. She was also not supposed to speak while he talked, but it took a conscious effort of will to suppress every syllable of encouragement or simple acknowledgement—every ah ha, uh-huh, oh, mm-huh, and hmmmm. But the worst was the enforced eye contact. It was simply not natural to stare steadily into someone’s eyes while you talked at them. It was faintly aggressive, a sort of challenge: What do you think of this, hey?You dummy, she told herself. This was surely the point of the whole exercise. This was what they were supposed to discover: that communication was a two-way street, that listening was not passive but active, that body language was half the message, that trying too hard to listen was precisely what prevented you from hearing—that, in Jim Bird’s terms, striving was what kept you from living. Of course! She smiled, then blushed, afraid that Brad would misconstrue her smile. He too, she now saw, was grappling with the eye contact: the effort of not looking away was draining his face and his voice of all expression. What he seemed to be telling her—with eerie, almost sinister dispassion—was that he was tired of hurting women.

“Time’s up! Now who wants to share their insights on this learning?”

As usual, no one put up their hand right away. Margo, having solved the lesson, did not want to deprive the others of a chance to figure it out, and stayed silent.

Eventually they began cautiously to lift their arms, and Ethan lowered his prayer-clasped hands and pointed to them one by one.

“I really enjoyed that.”

“Me too.”

“Excellent,” said Ethan. “Can you tell me why?”

“I don’t know. It was different?”

Ethan nodded, grimly encouraging, like a physiotherapist watching a car crash victim take their first painful steps. “How was it different—anyone?”

“It was more natural.”

“I felt that by not interrupting all the time I could really hear my partner.”

There was a general murmur of agreement.

“I felt that when I was talking I was really paying attention to what I was saying. I was worried I wouldn’t know what to say, but by looking Lottie in the eyes, I was able to concentrate—and it just came to me.”

Ethan beamed. “Because your underself—your true self—was doing most of the work.” His gaze, like a camera zooming out, diffused itself across everyone in the room equally. “By not looking at the outfield or the dugout but keeping our eyes firmly on the ball, by not pushing ourselves towards anything or pulling anything towards ourselves, by not fighting the stream of the now but letting it carry us, we are able to flow—to let go—to let it happen. Excellent! Anyone else?”

“But I didn’t get that at all,” Margo sputtered.

“Hands before ‘ands,’ please.”

Annoyed, she lifted her hand minimally from her lap, then threw it up over her head, but Ethan only went on staring at her expectantly.

“By focusing so hard,” she said slowly, aware that she was plucking her words from nowhere, “by trying so hard to listen, to pay attention, I just ... drowned myself out.”

There was another general murmur of agreement, identical to the first.

“Aha.” Ethan smiled imperturbably. “I think we’re up against the difference between effortful focus and effortless focus. Being in the now with your partner is not about trying to listen. It is ... about ... listening to try. Next time,” he said lightly, as if it were the easiest thing in the world, “relax.”

*

Already, by the end of the second day, Margo realized that she was at the wrong seminar. She had not, on Sunday night, believed Jim Bird when he had said as much, for that, she assumed, was just a piece of rhetoric. It was like when spies in movies said, Don’t trust anyone—not even me. Their bluntness, of course, was calculated to win your trust.But now, alone in her hotel room, some of what he had been saying came back to her, with troubling implications.

“The only possible kind of happiness is happiness with who you are.”

“You can’t change yourself—your self is a self, after all! You can only be yourself.”

But that was nonsense. She’d changed herself radically, and often. She was who she chose to be. Her self was what she made it.

She picked up the phone, then put it down. She ran a bath, but let it grow cold. She looked out her window and felt sad. She stood at the window in the hotel bathrobe and looked out at the sky growing dark over the city’s lights and in her mind’s eye saw herself standing at a window in a hotel bathrobe looking out at a dark sky above a city’s lights, and she felt sad. Brad and a few others were having drinks downstairs in the bar but she did not feel like talking to anyone. Her face needed a rest.

She sat on the bed and flipped through the seminar “material” and, for the first time, the Jim Bird books that Danielle had found at the library for her. (As a joke, Margo supposed, Danielle had also brought home The Will and The Won’t, Bird’s old book on Nietzsche; but this Margo had left behind—not so much because she believed Nietzsche had been a misogynist and proto-Nazi (which she did), but because she found it stuffy and unreadable.)

“The drive towards self-improvement,” she now read,

is a disease born out of self-hatred. You can’t desire to improve yourself without desiring to change yourself, and you can’t want to change yourself without hating the way you are. But what does it mean to hate yourself? It means one part of you hates another part of you. In other words, it means you’re divided. And as everyone knows, it’s united we stand, divided we fall.

NONSENSE, she wrote in the margin (in pencil—it was a library book). Then she pulled out her notebook and opened it to a clean page.

“Of COURSE I hate myself,” she wrote. “What self-respecting person doesn’t hate herself? Self-improvement is achieved through self-hatred. As a child, you reached for a hot stove and your mother slapped your hand. And quite right. But if your mother was not around, your body provided its own slap, maybe even more effective: the pain of burning yourself.

“This is how we learn: through pain, through remorse. When we do or say something stupid, or mean, or wrong, we mentally slap ourselves. Or anyway we should. We should hate ourselves, because none of us is perfect. (No, not even little old ME.)”

She put aside her notebook and called home. Luckily, Danielle was still pretending to be non-judgemental about the seminar, so Margo was able to complain without losing face.

“You don’t even get Jim Bird,” she said. “They break us up into ‘connect groups’ and stick us with a ‘connect leader’ all week.”

“I hate it when people use verbs as nouns,” said Danielle.

“I mean, there are three hundred of us, but for twenty-five hundred bucks you sort of feel entitled to—you know.”

“The guy on TV.”

Margo consulted her notebook, where she had jotted down some observations and criticisms that she thought Danielle might find amusing. “Our leader, though, this guy named Ethan. Must be all of thirty years old. He’s very casual. In fact you get the impression he’s playing a not very high-caliber game of Adverbs, and his word is ‘casually.’”

“Artfully disheveled hair?”

“Check. And ‘wild’ eyebrows that he must comb backwards. And he always wears his shirt unbuttoned to the navel. But it’s not very convincing. It’s a very theatresportsy portrayal of casualness. You don’t wear your shirt or your hair like that if you don’t care how you wear your shirt or your hair—only if you want people to think you don’t care how you wear your shirt or your hair.”

“Wait—to the navel?”

“Well he wears a T-shirt underneath.”

“Oh. Thank God. I had this image ...”

Margo lay back on the bed and looked up at the ceiling. “I don’t even know what I’m doing here.”

“Oh, you always hate it at first.”

“What? No I don’t.”

“The first couple of days you don’t know why you came, but by the end of the week it’s the best thing to ever happen to you, it’s changed your life, you’ve turned over a new— Sorry. But it’s true.”

“That’s ridiculous,” she said, but was vaguely troubled.

After she hung up, she turned on her laptop and opened her Resolutions file of three years ago. At about the time she had attended the Personal Pursuit seminar, her resolutions had been:

1. Write letter to Bertie

2. Learn Spanish

3. Wake up ten minutes earlier (weekdays)

4. Keep hands out of pockets (looks dowdy)

5. LOOK UP new words

6. More quality time with the daughters

7. Be goofier (take self less seriously)

8. Look in mirrors less

9. Exercise exercise exercise! (jogging?)

10. Floss (~3x week MIN.)

She read the list with dismay. Most of these resolutions could have been made last week. In fact, #6 was virtually identical to the #3 of today, and #10 had been upgraded to #7 (though now its demand had been decreased to twice a week). Spanish had been replaced by Norwegian—she had the crazy idea that she was going to translate Ibsen in her retirement—but she had, to date, learned nothing of either language. In fact she had made little progress with any of her old resolutions. She still battled with the snooze button most mornings, pulling herself out of bed at the last possible minute (she’d even tried setting the clock ahead, but, of course, knowing it was ahead, she counted on the extra time). She still had never jogged a day in her life (perhaps that needed to go back on the list?). She still gazed at herself in mirrors as often as ever, which probably only exacerbated her self-consciousness. But if she had been fighting self-consciousness, what about #4? She did not know if she still stuck her hands in her pockets more than she should, but it seemed a ridiculous thing to resolve not to do. But was her current #9 (“Smile with teeth”) any better? She felt an urge to add a new resolution to her list: “Stop making stupid, petty, vain resolutions!”

There was however one significant difference between her list of three years ago and her list of today. Back then her #1 resolution had been “Write letter to Bertie.” Now, of course, it was “Do not call Bertie.”

So she had changed, in at least one very striking way. That was reassuring.

It was funny, though. She could not recall what sort of letter she had been going to write.

Well, she always hated writing letters, so perhaps it had only been something quite inconsequential. A thank-you note for some gift, maybe.

But why had it been #1?

*

Wednesday.

They crumpled their pieces of paper into balls with the enthusiasm of kindergartners. Ethan drew a line on the floor with his toe and pointed at the garbage can in the corner.

“Toss them on in there,” he said casually, “and we’ll continue on to the next learning.”

The can wasn’t far away; most of the balls of paper went in. Margo, one of the last to toss, missed. She laughed, then felt she was trying too hard to show that it didn’t matter.

“Twelve,” said Ethan, sounding pleasantly surprised. “That’s more than we usually get. This is a good group! Hmm ... Tell you what. Let’s try it a second time—crumple up a fresh piece of paper if you don’t want to go rooting around in that old garbage can—and if everybody, I mean all fifteen of you, are able to sink it, we’ll take an early lunch, and I’ll buy coffees this afternoon. What do you say?”

This was fun; they were excited—but no one wanted to throw first. No one wanted to be the first to miss. Margo supposed this was all part of the lesson: You can’t win if you don’t try. And someone would miss, someone would have to be the first to miss. It might as well be her; it would take the pressure off everyone else. So she stepped up to the line and, with a humorous grimace, carelessly threw away her paper ball.

It went in. Everyone cheered. She curtsied.

Sonja, the shy single mom, threw next. It fell short. There were hums of sarcastically exaggerated disappointment and good-natured sighs to show Sonja that it was just a game, that no one really cared.

“That’s okay,” said Ethan, “but you know what? Let’s keep going. If the rest of you, all thirteen of you, get them in, the offer stands.”

In the end, he persuaded everyone to throw again. Altogether, only five went in.

“Sorry, gang,” said Ethan, smiling and shrugging his shoulders impishly to show that this was exactly what he’d expected to happen—that this was, in fact, all part of the lesson. “Well, I think there just might be time for one more learning before luncheroo.”

There were, on cue, a few mock-groans.

“So let’s all sit back down and open our material to page thirty-seven ...”

Most of the time, it’s not that we’re not trying hard enough. Most of the time it’s trying too hard that defeats us. Desperation poisons all our efforts:

- We’ve all met that person, at the office or at a party, who wants desperately to be liked. But what’s more unlikable than desperation?

- One person, desperate for a promotion, goes into their evaluation with sweat dripping from their brow. Another person, who doesn’t care whether they get the promotion or not, goes into the evaluation with easy confidence, casual indifference. Who gets the promotion?

- An athlete wants desperately to win, so they clench every muscle in their body and tie themselves in knots with needless tension.

- Your golf game (or squash game or basketball game) is going very well, you’re playing much better than usual—until you notice that you’re playing well, and think desperately: “If I can just keep this up, it’ll be my best game ever!” That’s when, of course, you “choke.”

- You can’t sleep at night. You’ve got an important appointment tomorrow and you really really need to get some shut-eye. The later it gets, the more desperate you feel: “If I fall asleep now I’ll still get five hours.” “If I fall asleep right now I’ll get almost four hours.” “Oh God, I need at least three hours!” But the harder you try to sleep, the more desperate you get, and the more awake you feel.

Desperation—that is, wanting something really badly—is like a fear of dogs. Dogs only attack you when they smell fear. So being afraid of them is the worst possible thing you can do! And wanting something badly is possibly the worst way to get it.

An old adage says, “Whether you think you can or think you can’t—you’re right.” In other words, the confident are successful because they’re confident, and the unconfident aren’t because they’re unconfident. Confidence is always justified—and self-doubt is always justified, too.

Well, you could also say, “Whether you’re afraid of dogs or not, you’re right.” But instead of “dogs,” think “failure.” Wanting badly to win is a kind of wanting desperately not to lose, and is the quickest way to failure.

Let’s face it: You can’t program yourself to be confident. (What could you possibly say to yourself? “Be confident, you loser”?) Confidence and success only come out of your true self in pursuit of its real dreams. To want something really badly and to try desperately to get it is a kind of bad faith, a self-betrayal, a backhanded admission that you’re not completely sure you can get it, or deserve to. But when your true self is chasing after your true dream, the effort is effortless, and there’s never any doubt.

Write down ten examples of things you’ve failed to get or goals you’ve failed to achieve because you wanted them too badly or tried too hard. (Use the back of this page if you need extra space.)

Margo did not believe she had ever wanted too badly or tried too hard; in fact, she did not believe such a thing was possible. All Ethan’s and Jim Bird’s assertions that nothing could be achieved through direct effort only strengthened her conviction that anything could be achieved through direct effort. Because they kept assuring her that she was powerless, she became quite certain that she was omnipotent.

(In the same way, of course, Jim Bird, after reading so many self-help manuals that assured him he was omnipotent—“Using the power of decision gives you the capacity to get past any excuse to change any and every part of your life in an instant!”—became only more certain that he was powerless. This is often what we do when confronted with an idea that conflicts with one of our beliefs: we exaggerate the idea, and exaggerate our own opposing belief; we make the familiar idea white, and the foreign black. This makes the new idea both easier and more enjoyable to combat. As Nietzsche said, even bad music and bad reasons sound fine when one marches off to fight an enemy.)

Margo ignored the instructions. She no longer even bothered trying to find the self-empowerment lesson hidden behind the self-acceptance doctrine; she simply wrote down whatever was on her mind. At the moment she did not want to think about the past, or mistakes she’d made, or her regrets. She wanted to think about the future. Wasn’t that what she was here for?

She drew a horizontal line, representing her past, that, at the point of the present, branched into several arrows representing the future. Beside the arrows she drew question marks. Then beside the question marks she wrote down what she saw as all the possibilities.

Travel. (Norway? Korea?)

Acting again. (She had never been happier than when acting. But would this really be a change—or a regression?)

Horseback riding. (She had never even been near a horse. Would she like it? Well, it would be something different.)

Real estate agent. (Her friend Nyla seemed happy.)

Write a novel. (Because none of her plays had been produced in a long time, she believed that theatre was a dying art.)

Divorcée.

She stared at this list for a long time.

*

Thursday.

“Your conscious mind,” said Ethan, “is like a dog on a leash. It sniffs this and that and goes running after it.”

To illustrate his point, he sniffed demurely in several directions. There were titters. Margo and Brad exchanged a wide-eyed look.

“But our unconscious mind, the sum of all our deepest wishes and dreams and ... what else? Just shout it out.”

“Hopes!”

“Our real self?”

“Life-scripts!”

“Desires?”

“Okay, yes, definitely, but what I’m looking for is—”

“Limitations?”

“Fears!”

“That’s it! Yes, the unconscious is the sum of all our hopes and desires definitely but also yes let’s face it our fears, and our fears, let’s recall yesterday’s learning, aren’t necessarily what?”

“Bad!”

“Uncomfortable?”

“Well yes, our fears aren’t necessarily bad, though they can make us uncomfortable, but that’s okay because our comfort zone is what? Everybody!”

“Comfortable!,” Margo and Brad shouted along with everyone else, but with a sarcasm that was detectable (or so they believed) only to each other.

“That’s why they call it a ‘comfort zone,’ folks,” Ethan deadpanned. “It’s comfortable. And our fears and our dislikes are signals of discomfort, but discomfort is useful, isn’t it. It shows us the limits of our comfortable zone. Like we said on day one: The mind can’t make a heaven out of hell or a hell out of heaven—sorry, Milton. What you like is what you like, what you hate is what you hate. If you hate broccoli, and who here hates broccoli, show of hands? Yeah well, welcome to the club, ha ha. If you hate broccoli you don’t say to yourself: Gee, I sure wish I liked broccoli, then I could eat a lot of it!”

Brad murmured in his Ethan voice, “I sure wish I was gay, then I could have sex with all those beautiful men!”

“Okay,” Ethan was saying, “so the unconscious mind, which is made up of your dreams and your fears both, your unconscious mind is the master holding the leash. That’s why we never get far. Unless we let go and let our master lead the way, we’re only going to succeed in choking ourselves on that leash.”

He had them write down seven “definers,” or critical moments in their lives, then analyze whether they had acted as the dog or as the master. Had they run off incontinently towards what they thought they wanted, or had they pursued their true desires? Had they done what their intellect said they should, or that which their heart said they must?

This distinction was incoherent to Margo. Why should the two necessarily be at odds? Why couldn’t her conscious, rational decisions at least occasionally correspond to her unconscious wishes? In fact, wasn’t the process of decision-making, of thinking a matter through from every angle before acting, wasn’t this precisely the way the conscious part of the mind figured out what the unconscious mind, or the whole self, wanted? She put up her hand.

“Sorry Ethan, and everybody, but forgive me if I’m wrong here, but don’t you sometimes do exactly what you want to?”

“Sure. That’s what we mean by pursuing your true desire, Mar, acting with your true self.”

“But what I mean is, don’t you sometimes want to do just what you should do? Don’t you sometimes want to do what is right? Doesn’t your ... dog sometimes go the same way as your master?”

“Can I answer that Ethan? Well Mar, the way I see it is last year for example I set this goal for myself? That I would make two hundred and fifty thousand dollars?” There were perfunctory murmurs of recognition; Lottie mentioned this figure almost every time she spoke. “Well I didn’t achieve it and I’ve been trying to figure out why. Now it occurs to me that one of my definers was this business deal I got involved in. I won’t go into the details,” she said, then went into the details. “Anyway the point is, and Ethan correct me if I’m wrong here, but wasn’t that my conscious mind choosing to get into that deal because I wanted it too badly? Wasn’t that my dog running off ahead of my master? Like, instead of letting two hundred and fifty thousand dollars happen, I was making it happen?”

“Excellent, Lottie.”

For not the first time that week, Margo felt like she was drowning in some invisible fluid. “But what if the deal had worked out?”

Ethan and Lottie stared at her blankly. She turned to Brad for support. He gave her a steady, compassionate look, as if she were some crazy but lovable aunt who should be placidly tolerated. She hated him at that moment.

Later, at lunch, however, he agreed with her. “It’s dumb, all right. Because if your unconscious desires are really unconscious, you can’t ever know what they are. You can say anything is your ‘true’ self. I came to this thing because I have a problem with commitment. Every time I meet a new girl, I think she’s the one I want to commit to. But which is the true me: the one that sleeps around, or the one that wants to settle down? Should I be trying harder to be happy with the girl I’m with, or should I be trying to find the person I’ll be happy with naturally, easily? Does settling down mean settling? Should I force myself to stay with a girl even after I get bored? Is that what love is? But then what if I meet someone new, someone—hypothetically speaking—intelligent, attractive, mature. Someone I can talk to. Should I just ignore her, pass her by? What if this is the woman I’m supposed to be with? But maybe I’m just fooling myself. Maybe this is just my way of wriggling out of the old relationship. But is it even possible to make yourself be happy with someone?”

Margo was disturbed by the intensity with which he asked these questions. This was not just rhetoric. He seemed to expect some answer. She felt as though he were petitioning her for advice, and did not like the implications. The word “mature” had stuck in her mind, and to combat the flattering possibility that he was flirting with her, she decided to take offense: He thought she was wise, knowing, experienced! He thought she was old!

“Oh, what the hell do I know?” she said. “I’ve never been happy, not really. Not for any length of time. Anyway, who wants to be happy? Have you met a happy person lately?”

“I don’t know. Ethan?”

“Exactly. Happy people are morons. Morons are happy. Anyway, forget all that hogwash about your true self. You don’t ever know how anything’s going to turn out. All you can do is think it over and then do what seems right. Do what you want.”

“But how do you know what you want?”

She looked at him. What did she want? How could she know? What test could she perform? Introspection was a myth; her consciousness, like her eye, could never be its own object. Her self—that dim, immeasurable, unlocatable, forever forward-facing, outward-looking self—could never know of what it was made. She could only judge her desires retrospectively: whatever course she finally took, that must ultimately be the one she had most wanted to take. Thus her behavior was an infallible record of her desires. It was, then, in other words, impossible to act contrary to her own wishes. For even to try quite conscientiously to do so was to make acting-contrary-to-her-own-wishes itself her wish! At that thought, she almost heaved a sob for all the pleasures she had denied herself, all the paths she had not taken, throughout her life—because had she taken them, they would have, by that very fact, been that which she had most desired. But no, that made no sense. Because, by the same logic, she must have desired the denials more than the acceptances.

What did she really want? If the only way she could assess her own feelings was by reviewing her actions, then no one could know her less than she did, because she, unlike others, had to rely on memory, on photographs and mirrors, to get glimpses of herself. And why should she feel such loyalty to a stranger? It didn’t matter at all. Life was a map without wrong turns. She could do whatever she wanted!

Agh, but what did she want? She couldn’t use her past as a guide, for even if she could detect there some pattern to follow, she would only be condemning herself to doing as she had always done. This would only prove Jim Bird’s tenet, that we cannot change ourselves.

“Whatever you do,” she blurted at last, with a smile she did not have to measure out in advance, “whatever you do, that’s what you want.”

Brad laughed. “But what to do?”

*

That evening after class she went up to her hotel room and called Bertie.He didn’t answer. She realized with a start that he probably wasn’t home from the shop yet. This prosaic explanation seemed disproportionate to the momentousness of her act. She had finally broken down and called him—and he wasn’t even home. How was this possible?

Her voice was still on the answering machine. She did not leave a message.

*

Friday.

The next night she was sitting at her assigned table in the banquet room, scrunching up her napkin and getting unobtrusively drunk, when John came over and asked her to dance.

She had been in a good mood most of the day. She felt, as she supposed she always felt at the end of a seminar, that her life was going to be different from now on. This feeling was not attributable to anything Ethan or Jim Bird speaking through Ethan had said. Rather, two thoughts from her conversation with Brad the day before kept returning to her. The first was that whatever she did was what she wanted to do. The second was that she had never been happy.

And if you’ve never been happy, said her mind gloatingly, what makes you think you ever will be happy?

Okay. She would never be happy. She was incapable of it. This thought, curiously enough, made her feel quite content.

A placebo works because we expect it to work; that is, having swallowed it, we can stop fighting, or fleeing, or shrinking from the pain. Blake once said, “He who binds to himself a Joy / Doth the winged life destroy”; and we could perhaps add, “He who thrusts from himself a Pain / Doth invite the same again.” Just as chasing after happiness is the surest way to lose it, running from unhappiness is the surest way to bring it on. Margo, by resigning herself to her unhappiness, no longer had to fight it.

And since she would never be happy, no matter what she did or who she was with, there was no reason not to go back to Bertie—with whom she was comfortable, and about whom the worst that could be said was that he loved her unconditionally, and would not object, would perhaps not even notice, if she gained twenty pounds eating strawberry ice cream and cuddling with him on the couch in front of the television.

She wallowed in the idea of herself as fat and lazy and hedonistic—and alternately in the idea of herself as fundamentally, inescapably miserable. That morning, she slept in, was late for class, slouched into the room with her hands in her pockets, mumbled an incoherent (and insincere) apology, did not raise her hand when she had questions or objections, took no care to smile with her teeth, and, in short, enjoyed hating herself thoroughly.

But then in the afternoon, as a feel-good valedictory activity, Ethan had them write compliments and stick them on one another’s backs. Margo’s equilibrium was disturbed first by the fact that she could find so many kind things to say. She had felt all week like an outsider, alone with her doubts and her criticisms and at odds with the group. She realized now that in many ways she felt only respect and admiration for her classmates. When she had first arrived on Sunday night she had, as if by default, been irritated by how sane and healthy, how effortlessly normal, everyone looked. By “normal” she did not mean happy, she realized, but something more like unconfused, coherent. Unlike herself, everyone here seemed to have figured out long ago the knack of being themselves. Like characters in a play, other people were incapable of acting out of character. They did not dither or second-guess themselves (or if they did, it was only characteristic of them). Now, however, five days later, she was more impressed by her classmates’ imperfections and uncertainties. Some of them, she had learned, were grappling with real problems. Louise was being tormented by an estranged teenage son; Carla was fighting for custody of her five-year-old daughter; Sonja was trying to balance motherhood, work, and an incipient romance, all without guilt; Shelly couldn’t get in an automobile again after an accident and had lost her job; John was trying to find a passion that could replace the career that he had been forcibly retired from. Margo felt that her own obscure, obsessive worries (what to do with her teeth!) were trivial next to theirs, and she found it easy to write heartfelt compliments for each of them.

She was even more disturbed by the comments that she received. Not because they were negative—they were all, if anything, embarrassingly positive—but because they were so consistent. The same adjectives and phrases kept reappearing. The composite image that they conjured up was, startlingly, of a woman not so very different from the one that Margo aspired to be: strong, outspoken, courageous, opinionated, independent ...

But somehow this did not please her. Once, she and Bill and the daughters had been playing Adverbs, and Bill had done an impersonation of her. He had acted “Margo-ly” or “Mommily” by rubbing his hands together a lot and concluding all his sentences with a fruity “... I think.” It could not have been less vicious, but she was deeply offended by this caricature of her. She had not realized that she rubbed her hands together when she spoke or that she said “I think” more often than anyone else. These were mild, inoffensive mannerisms to be sure, and perhaps she should have embraced them; but once she was shown them they became conscious mannerisms—that is, affectations. Thereafter, whenever she caught herself rubbing her hands together, she felt that she was doing an impersonation of herself.

That afternoon, too, she felt ridiculous, as if she’d been praised for playing a part well—instead of just being herself.

*

She had already been asked by Brad to dance, and had said no. Feeling guilty, if also a little flattered, by his hangdog look, she had explained herself expansively.“Dancing these days is all improv. You just get out there and do whatever you feel like, with or without a partner. But when I was young”—she pulled out this phrase with a defiant absence of irony—“we danced to a script. You had to learn the steps first, but at least you always knew what to do. And then you could perform. There’s no performance in this kind of dancing,” she said, gesturing with repugnance at the few people twitching and jerking solipsistically around the dance floor. “It’s either meditation or ... showing off.”

So Brad had gone off and found someone else to dance with—a blonde girl from one of the other connect groups whom Margo had not noticed before. Watching them, she was flabbergasted by the extent of her bitterness. This was the archetypal story of her life; this was the hell she had created for herself: to be always looking in from the outside; to be always waiting in the wings of life, never to be onstage. She could of course change her mind, go and ask Brad for that dance. But she could not be the sort of person for whom that would be the natural choice. She could never be the sort of person who would have said yes in the first place. She saw her limits but now was no longer wallowing in them. She hated herself keenly, and hated all the world, which at that moment seemed to her to be made up entirely of dancers.

Now John was asking her to dance. It was a slow dance; she would not have to improvise. She was surprised at how strongly she wanted to say yes, just to spite Brad.

“I’m sorry, John,” she began, then stopped herself. She crumpled up her napkin and threw it into the middle of the table. “Will you hold that thought?”

She strode across the room. The vast banquet hall was a glittering ice cavern, and she skated across it. Though she might fall, she couldn’t hurt herself: she would only slide off whatever she collided with ... She was drunk.

Jim Bird was talking to one of his connect group leaders, but she spoke anyway.

“I’m sorry to interrupt here, but Jim ... well, shit—how would you like to dance?”

He looked up at her with confused eyes, a mouth unsure whether it should smile or not.

“I’m sorry,” he said at last, “but I don’t actually really dance.”

“That’s what I thought,” she said with dour self-pity. But by the time she had recrossed the room she was remembering her tone differently. That’s what I thought, she’d said—but joyously, almost triumphantly, as if she had scored a point against him.

I would, said Nietzsche, only believe in a God who knew how to dance.

She danced with John, then found Brad and danced with him. She drank some more and fussed with her napkin. She ate chocolate brownies. She shared a cigarette with Brad in a stairwell or a parking lot. She had a long conversation with Lottie. She discovered a new way to dance: she moved until she did something that felt silly, then repeated that movement methodically, rhythmically, and made it her own. In the bathroom she wiped off what remained of her lipstick and laughed at something someone said. She would die one day, she supposed. She still missed Bill. She loved her daughters; she had no regrets. She liked herself, and wanted to change. She was happy, and she made a list of resolutions on her napkin and stuck it in her purse. Her ears were ringing. Brad shouted in the elevator. His breath was warm. Life was a piano, but the keys were out of order. She was paddling an iceberg. Healthy self, heal thyself. She laughed at the boyish reverence with which he took off all her clothes.

But she was only pretending.

*

Saturday.

The physicist Schrödinger (unlike Jim Bird, I do not think Nietzsche is the only show in town) once put forward the idea that consciousness only accompanies novelty. To the extent that an organism already knows how to do something, or has developed a routine of reflexes or habits to deal with a known situation, to that extent it is unconscious—as when we walk or drive down a familiar street without even being aware of our surroundings. Only when some new element, some differential, pops up, demanding to be dealt with in a new way, are we fully awake. The world around us fades from consciousness as we learn how to deal with it.

But not knowing how to deal with the world is, to say the least, distressing. Consciousness, then, is distressing. According to Schrödinger, the most aware individuals of all times, those who have formed and transformed the work of art which we call humanity, have always been those who have suffered most the pangs of inner discord. “Let this be a consolation to him who also suffers from it. Without it nothing enduring has ever been made.”

The basis of every ethical code, he goes on to say, is self-denial; there is always some “thou shalt” or “thou shalt not” placed in opposition to our primitive will. Why should this be so? Isn’t it absurd that I am supposed to suppress my natural appetites, disown my true self, be different from what I really am?

But our “natural self”—what Jim Bird calls our “true self,” “living self,” or “underself”—is just the repertoire of instincts and habits we’ve inherited from our ancestors. And our conscious life is a continued fight against that unconscious self. As a species we are still developing; we march in the front line of generations. Thus every day of a person’s life represents a small bit of the evolution of our species. Granted, a single day of one’s life, or even any one life as a whole, is but a tiny blow of the chisel at the ever-unfinished statue. But the whole enormous evolution we have gone through in the past, it too has been brought about by a series of just such tiny chisel blows.

The same is true of the individual. At every step, on every day of our life, something of the shape that we possessed until then has to change, to be overcome, to be deleted and replaced by something new. The resistance of our primitive will—shouting, “Do what’s easy! Do what you’ve always done!”—is the resistance of the existing shape to the transforming chisel. For we ourselves are chisel and statue, conquerors and conquered at the same time. Deciding what to be, becoming what we are, is a true continued self-conquering.

*

What the age-old debate over free will boils down to, it seems to me, is this: Can we sometimes do what is hard, or are we condemned to always do what is easy?The materialistic determinists, men like the famous philosopher who kindly wrote that introduction to James R. Bird’s book on Nietzsche, believe that we always do what’s easy. We are physical systems, and physical systems always follow the established routes. Clocks do not run backwards, water cannot run uphill, and a neuron firing in our brains can by no effort of its own pull itself up by its bootstraps and act counter to its habit. It does what it’s supposed to, what it has always done.

I do not know much about the brain. I know that neuroscientists like to eulogize it as the most complex three pounds of physical matter known to exist in the universe—but always with the implication that it’s still just a lump of physical matter, that we are still just fancy machines. (As Nietzsche put it, “The living being is only a species of dead being.”)

But it seems to me that the material determinists want to have it two ways. We are our brains, they tell us; and (therefore) we are in thrall to our brains.

But if we are our brains, then we are not in thrall to our brains. You cannot point to one piece of our brains, one neuron among billions, and, noting how regularly and unimaginatively that piece behaves, thereby disprove unpredictability or imagination on the larger scale. It would be like pointing at my arm, which moves every time a certain pattern of electrical impulses reach it from my brain, and saying, “Your arm is not free to move or not move; therefore you are not free”—when I was the one, each time, who freely decided to move my arm in the first place. It would be like pointing at a soldier who always follows orders and concluding that the general has no power, or that the movements of the army are fatalistically determined.

The patience of the bricklayer (as a poet once said) is assumed in the dream of the architect; the obedience of the soldier is assumed in the freedom of the army. We think with our whole brain, and we need our individual neurons to follow orders predictably and reliably so that we can call up ideas or memories or biases or vague feelings or pros and cons whenever we need them. But what the whole system is going to do with all of that material, what the universe in your skull is going to produce or conclude or decide after mixing all those things together for a while, is astronomically unpredictable. Our decisions, our free choices, are nothing if they are not the fruit of deliberate thought. The more that we need to think about something before we act; the more parts of ourselves brought into play in making a decision; the more chemicals that get put into the beaker, the less certain the result, and the freer our will becomes.

I am the most complex three pounds of physical substance known in the universe? Okay. That sounds about right. That, to me, satisfies my requirements for a robust notion of a freely willing self. To me, a vast tumultuous physical system in disequilibrium but churning itself towards some unforeseeable state of temporary or relative stasis is a very good model of free will.

Sometimes, it is true, one desire or drive or motive will be much stronger than the others; it will be no contest. But do we really want to say that I am (as the famous philosopher puts it) “doomed by determinacy” to leap into traffic and snatch up my child? Wouldn’t it be truer to say that I am acting in this situation with my full self, my true self? Maybe some decisions aren’t really decisions. Maybe a lot of the time we go around on autopilot. Often our choices are obvious. But often they are not. That is when, as Nietzsche says, our various semi-independent drives must fight it out for supremacy. Consciousness is a battleground. But what we must remember, if we are not willing to foredoom the outcome, is that in any large enough street brawl even the underdog can win.

How does this happen? How does that one small part of ourselves whispering “No, do what’s difficult, do what’s right” ever emerge victorious? I think it is not through strength, but through perseverance.

Not enough has been said about the width—or rather, I should say, the thinness—of free will. We only ever act in the moment. But most of the decisions we make in life—whether or not to have children, whether or not to change one’s career, whether or not to leave one’s spouse—are ongoing decisions, spanning weeks, months, or years. Even the deceptively simple decision to give up strawberry ice cream, for example, must be remade continually—basically, every day for the rest of your life. No matter how fiercely you ball up your fists, clench your teeth, and simply will, once and for all, with all your might, that so help you God you will never eat another spoonful of strawberry ice cream ever, it is not enough. It cannot be enough, because there is no once and for all. There is once, and then there are all the other onces. Here’s another way of saying it: There are no big chisel blows, only many, many tiny chisel blows. Carrying out a resolution is like memorizing a poem, or learning to play the piano. It cannot be done in one single burst of will.

Once, many years ago, Margo was acting in a play. She came out of a wardrobe change, stood in the wings, and began to shiver violently. She was wearing a slinky, insubstantial evening dress, and the theatre was cavernous and cold. Or perhaps she was nervous. In any case, she had about five minutes to get ahold of herself before her cue. When rubbing her arms and visualizing tropical climates didn’t work, she finally, in frustration, just willed herself to stop shaking. It was good that she had five minutes; she needed that much time.